How the national 2040 climate target can be achieved

Climate change is advancing rapidly. This makes it all the more important to effectively align economic, societal and political action with the goal of achieving greenhouse-gas neutrality in Germany by 2045. A new study by the German Environment Agency (UBA) shows that this target can still be reached. The short-term climate targets for 2030 must continue to be pursued consistently. By 2040, Germany must have an ambitious climate policy that puts the country firmly on track for greenhouse-gas neutrality. According to the UBA’s assessment, it is possible to reduce emissions by more than 90 percent compared with 1990, thus going beyond the requirements of the current Federal Climate Change Act.

“The coming decade from 2030 to 2040 is crucial to ensure that Germany achieves greenhouse-gas neutrality in 20 years,” says Dirk Messner, President of the UBA . “We must make the necessary decisions today in order to guide the various sectors towards their target goals.” Achieving this will require further development of the current Federal Climate Change Act after 2030.

The UBA shows what such an ambitious climate action roadmap could look like and which steps policymakers can implement in individual sectors and across sectors. It is important that interim targets and guiding frameworks are already aligned with greenhouse-gas-neutral economic activity and that no fossil-dependent pathways are created. Once development pathways are set and investments made, they can only be changed after long depreciation periods or at very high conversion costs. “Smart climate policy always keeps competitiveness in mind as well,” says Messner. “Germany and Europe can become pioneers of a strong, climate-neutral economy.”

Greenhouse-gas neutrality is achieved by minimising emissions at their source. For emitting sectors, phasing out the use of fossil fuels is the foundation for contributing to greenhouse-gas neutrality. On the basis of a consistent expansion of renewable energy, processes must be further electrified. Expanding and digitising the power grid is crucial both to transport the required volumes of electricity and to enable smart electricity use.

The expansion and decarbonisation of existing district heating networks form the basis for a greenhouse-gas-neutral heat supply and links the energy transition with the heat transition. The green hydrogen economy and its scale-up provide the foundation for transformation, particularly in industry, the chemical sector, the energy sector and parts of transport, such as shipping and aviation. As a future technology, it offers opportunities for innovation and mechanical engineering and can increase independence as well as security of supply for Europe and Germany. Realising this greenhouse gas mitigation potential requires planning certainty for businesses and private individuals within the energy transition.

“These changes demand a major effort for our country, but at the same time they open the door to future-proof prosperity and reduce the costs that runaway climate change entails. We need broad societal backing for this,” says Messner. “The transformation must not come at the expense of vulnerable groups; social hardships must be mitigated. At the same time, the economy needs a reliable policy framework to support this modernisation process.”

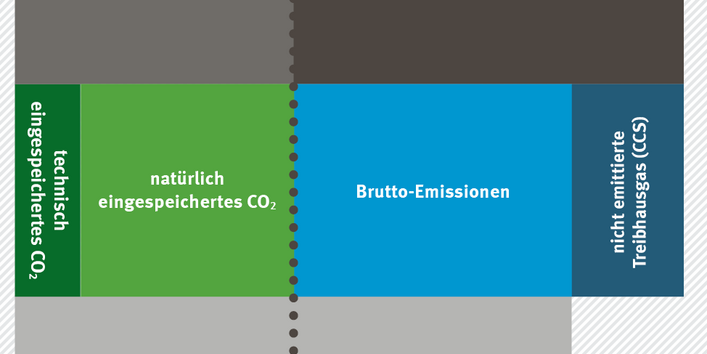

In parallel, carbon sinks must be expanded substantially to address unavoidable residual emissions. For this, the land use, land-use change and forestry (LULUCF) sector is indispensable. It stores large amounts of CO 2 when forests and peatlands are intact, agriculture adopts sustainable soil management practices, and long-lived wood products are used more widely in construction. The sector’s sequestration capacity is protected and strengthened by measures such as sharply reducing the removal of broadleaf timber, promoting forest conservation and climate-resilient forest conversion, and making long-lived wood products economically viable. Rewetting drained peatlands and optimising water levels in wetlands make a significant contribution to reducing emissions.

With the currently proposed Action Programme for Natural Climate Protection (ANK), the LULUCF sector has the opportunity to be put on track to achieving its targets. In combination with a moderate ramp-up of technological sinks, the land-use sector is essential for achieving the targets.