What is the regulation about?

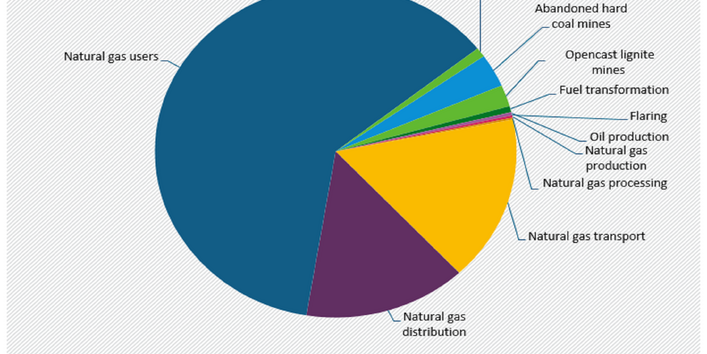

The EU Methane Regulation 2024/1787 requires fossil energy infrastructures operators to measure methane emissions regularly, eliminate leaks quickly and reduce the venting and flaring of gases. In Germany, monitoring is carried out by the monitoring authorities of the federal states, while the German Environment Agency is responsible for the annual emissions reporting. The regulation is coordinated by the Federal Ministry for Economic Affairs and Climate Action. The operators' emissions data is aggregated and published on this website. They are also included in international reporting on greenhouse gas emissions (in German). This creates transparency and enables a direct comparison with other countries.

The regulation not only aims at reducing direct methane emissions in Europe's energy sector. It also takes into account emissions from fossil fuels that are not generated in the EU, but occur before they are made available in Europe (upstream emissions). Thus, Europe can also work towards establishing minimum environmental standards in producing countries when importing fossil fuels.