Owing to changes in seasonal weather patterns associated with climate change, agricultural businesses are forced to adapt their management planning accordingly. The most favourable times for tilling, sowing and harvesting and for the application of fertiliser and pesticides have to be redetermined specifically for every year. Both direct and indirect effects of weather patterns play a crucial – albeit not the only- role in deciding which management operations should be continued and which should be terminated. As far as the direct effect of weather is concerned, it is, for instance, important to determine the most favourable time for tilling, and this timing is heavily dependent on soil moisture. Another example is the scheduling of sowing (drilling) in spring, because specific crops such as maize should not be sown until and unless the soil has reached a certain temperature. Indirect effects of changed weather patterns play a role in the choice of crop species and varieties (cf. Indicators LW-R-2 and LW-R-4) and the selection of crop rotations made by agricultural businesses in order to adapt to changing climatic framework conditions.

Such adaptation practices are basically nothing new in agriculture, as these challenges have always had to be addressed in carrying out management operations as they had to respond to the seasons and phenological development phases of crop species. Nevertheless, it is conceivable that the incidence of unpredictable weather patterns or weather scenarios is on the increase.

Apart from data on temporal changes in the development of plants, the DWD‘s nationwide phenological observation network also collates data on changes in management operations carried out in respect of agricultural crops. Depending on the management operation concerned, the influences on scheduling vary. Apart from weather patterns, there are usually several other factors to be considered. Of foremost relevance is the selection of varieties and crop rotation. Sowing can only commence after the previous crop – cultivated as part of crop rotation – has been removed. Organisational requirements in individual agricultural businesses may also play a crucial role. Depending on the cultivated area and the extent of a farm’s own machinery or the contractor’s machinery, management operations may have to be rescheduled. In other words, such decisions on rescheduling management operations in agriculture are not exclusively dependent on weather patterns. Nevertheless, relevant observations may provide useful pointers for adaptations in respect of management planning.

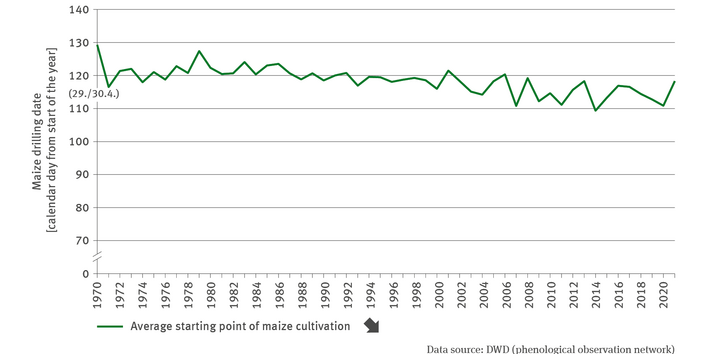

The cultivation of maize takes place typically in the course of April and May once the soil is warm, well dried and resilient, while the soil temperature amounts to roughly 8 to 10 °C. Sowing at the right moment is crucial for plant development, healthy growth and thus ultimately also for yields. In spring any effects due to management operations will be comparatively minor, and the influence of weather patterns play a more important role at that time, rather than at a time when management operations are scheduled for summer and autumn. Therefore the changes regarding cultivation dates in spring are a suitable subject for indication in the context of climate change, especially for summer crops.

Apart from the weather pattern in spring, the decision to sow summer crops also depends on whether and to what extent the catch crops were killed by frost during the winter months or by the end of winter. In cases where this cannot be safeguarded, additional work may be necessary in the preparation of seedbeds for the main crop of maize.

Over the past fifty years, maize cultivation started earlier and earlier. Judging by the mean of the past ten years, maize was sown more than a week earlier than in the 1970s, . It is also remarkable that since the turn of the millennium, there have been distinct fluctuations from year to year. Extremely early sowings occurred in the years of 2014 and 2020. At the same time, those years were characterised by an extraordinarily high number of days with soil temperatures of more than 5 °C (cf. Indicator BO-I-4).

Sowing maize early is advantageous insofar as maize requires specific amounts of warmth to become ripe enough for ensiling or to reach grain maturity for use as corn. Under these circumstances, the optimum harvest dates for silage maize can be reached earlier. As far as grain maize is concerned, a longer vegetation period usually results in lower water contents in the grain, thus achieving higher market values (cf. Indicator LW-R-3). Furthermore, sowing maize early can help significantly in curbing competition from weeds. Besides, early in the year the soil is protected better from erosion.

Apart from the planning and scheduling of management operations, there are other measures which play an important role in terms of soil protection and improving the growth conditions for crops: In order to buffer the worst of the impacts of extreme weather events, to avoid erosion, and to safeguard the replenishment of water and nutrients in dry periods, management operations have to maintain high infiltration rates as well as storage capacity for water and nutrients and a good aggregate structure in the soil. It is essential to maintain the organic soil substance or – where necessary – to improve it as required by site-specific circumstances (cf. Indicator BO-R-1). Stabilising measures in individual agricultural businesses can include the cultivation of catch crops, nurse crops, various species combinations, incorporation of harvest remnants, cultivation of perennial crops, organic fertilisation and adaptation of soil tillage. At a higher organisational level, the following elements are considered essential for adapting agriculture to climate change: feed and farm manure synergies, the integration and utilisation of perennial fodder plants in crop rotations, the conservation of grassland (cf. Indicator BO-R-2), maintaining the stability of mixed livestock-cum-arable farms as well as ecological farming and landscaping (such as agroforestry systems, contour management and beetle banks).