A terrain that has not been built on. is unfragmented and free from urban sprawl, is a limited and desirable resource which is much in demand and the object of competition among sectors such as agriculture, forestry, developers, transport infrastructure, nature conservation, the exploitation of raw materials and the generation of energy. The designation of priority and restricted areas is a tool used by spatial planning in order to guide the development of land use including the curbing of new land take-up, and to balance competing claims on land use. After all, it matters to conserve or further enhance ecosystem services important to humans and wildlife alike.

In connection with changing climatic conditions, these ecosystem services address the potential of unsealed surfaces to allow the infiltration of precipitation and also – especially at times of heavy rain or flood scenarios – to provide temporary water retention services. Alluvial meadows free from building developments give rivers space to expand and can take pressure off the underlying areas of river basins at times of flood (cf. Indicators BD-R-2, and RO-R-6). In bioclimatically stressed spaces, the passage of fresh and cool air to residential areas is paramount. On the periphery of conurbations, air is apt to cool off faster in the summer months above meadows and arable land than in residential areas. Air channels such as parts of open valleys transport the cool air to neighbouring residential areas thus mitigating any thermal stress (cf. Indicator RO-R-4). As far as agriculture and forestry are concerned, and also in respect of the harvesting of renewable raw materials, it is above all relevant to protect fertile soil and productive land in a sustainable way for the future. Moreover, animals and plants depend on open spaces and unfragmented, networked landscape structures for their habitats. If habitat conditions change as a result of climate change, fauna and flora are in need of functioning biotope networks enabling them to adapt.222

Land that is free from buildings retains its potentials, or such potentials are relatively easily restored, if the change of use involves agricultural or forestry purposes, provided the type of new land use is, for example, the generation of renewable energy or multiple usage such as agri-photovoltaics or nature conservation, whereas the potentials would be permanently lost, if the new land use were to involve developing the terrain for settlement or transport infrastructure or if it were to involve any form of mining such as large-scale quarrying projects. The reduction of areal land take-up – with its various adverse effects – can therefore be seen as a general adaptation measure the implementation of which can be supported by means of the toolbox available to spatial planning.

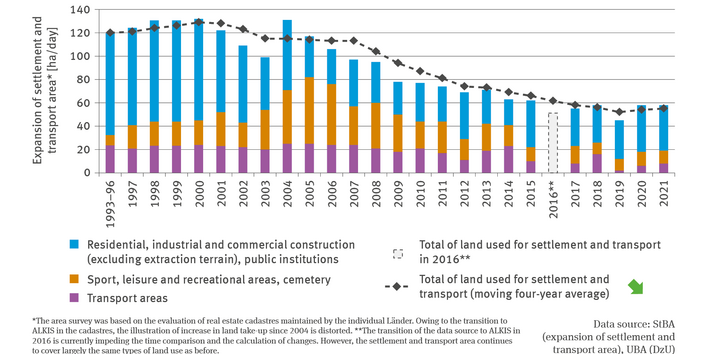

At the same time, curbing any new land take-up is also one of the key sustainability objectives pursued by the Federal Government. Originally it was intended for any new land take-up for residential and traffic purposes – as laid down in the national sustainability strategy adopted in 2002 – to be reduced to 30 ha per day by 2020. The updated German Sustainability Strategy223 now intends for the daily increase in the take-up of residential and transport terrain to be reduced to less than 30 ha by 2030. The BMUB’s Integrated Environmental Programme adopted in 2016224 even exceeds this target. With a view to the target path for the implementation of the EU’s resources strategy and the climate protection plan 2050 which envisages that by 2050 the transition to a circular land use management will have been completed and any new take-up of land will have been reduced to net zero, a value of 20 ha per day has been set as an interim target for 2030.

In contrast with the powerful expansion of residential and transport areas in the early 2000s, the new take-up of land has more than halved in recent years. While the moving four-year average was then in excess of 130 ha per day, the mean of the period from 2018 to 2021 amounted to ‘just’ 55 ha per day. There are several reasons for this. Essential regulations were tightened up in the construction and planning law. At Federal, Länder and municipal level, efforts were redoubled in the endeavour to be more provident in the use of land resources. The weaker economic development and economic crises such as the banking crisis, combined with changes in demographics, curbed the private and commercial demand for buildings.

Above all, the sector covering residential, industrial and commercial construction (excluding extraction terrain) as well as public institutions contributed to the increase in settled areas in the period from 2018 to 2021. Latterly, this sector grew in 2021 with figures of approximately 39 ha per day, residential housing making the biggest contribution to this growth. Sport, leisure, recreational and cemetery areas contributed another 11 ha to the settled terrain; transport areas increased by just under 8 ha per day in 2021. In that respect, the main driver was the areas used for road transport.

The increase in land use for settlement and transport areas in terms of the four-year average in the past two years has interrupted the mostly continuous decline in new land take-up which had prevailed since 2000. Admittedly, various conversions and transitions in the performance of area surveys during recent years have limited the comparability of data. Nevertheless, the development emerging in the course of recent years makes it clear how challenging the task is to achieve the objectives set in the German Sustainability Strategy and the Integrated Environment Programme. Further endeavours are required, also with regard to the effects of a provident handling of land resources on climate change adaptation. Thanks to its toolkit consisting of informal and formal tools, spatial planning can make valuable contributions in this respect, for instance by means of circular land use concepts. Any additional efforts required to achieve provident land use will have to take account of potential impacts resulting from climate change. Among other things, it is not acceptable that an intensified settlement development in an inward direction, that is to say, by means of land recycling or retro-densification, should be allowed to make the existing bio-climatic stresses worse. In fact, building development would require the negotiation of suitable solutions and compromises in the course of in-situ structural development, so that the often competing objectives and challenges are met.

222 - Pannicke-Prochnow N., Krohn C., Albrecht J., Thinius K., Ferber U., Eckert K. 2021: Bessere Nutzung von Entsiegelungspotenzialen zur Wiederherstellung von Bodenfunktionen und zur Klimaanpassung. Umweltbundesamt (Hg.). Texte 141/2021, Dessau-Roßlau 360 pp.

https://www.umweltbundesamt.de/publikationen/bessere-nutzung-von-entsiegelungspotenzialen-zur

223 - Die Bundesregierung (Hg.) 2021: Die deutsche Nachhaltigkeitsstrategie. Weiterentwicklung 2021. Berlin, 385 pp.

224 -BMUB – Bundesministerium für Umwelt, Naturschutz, Bau und Reaktorsicherheit (Hg.) 2016: Den ökologischen Wandel gestalten – Integriertes Umweltprogramm 2030. Berlin, 127 pp. https://www.bmuv.de/publikation/den-oekologischen-wandel-gestalten