Permanent grassland refers to meadows and pastures which are either harvested by mowing or grazed by livestock. This is where grass is cultivated and herbaceous plants are cultivated as permanent crops. As a result of permanent ground cover, humus enrichment and species diversity, permanent grassland provides – especially compared to arable land – numerous favourable impacts, and it protects soils from the projected adverse effects of climate change. Especially the risk of soil loss from impacts of wind and water (cf. Indicator BO-I-3) is considerably reduced where soils are under grassland. In cases of heavy precipitation, the precipitated water has a much better chance of penetrating a field with permanent grassland cover than a field of arable soils devoid of vegetation. Moreover, humic contents in grassland are higher (cf. Indicator BO-R-1). Consequently, the conservation or even expansion of permanent grassland, especially on sensitive sloping ground used for agricultural purposes or in floodplains, constitutes a suitable measure for protecting soil even where it is affected by climate change.

Likewise, the loss of soil owing to converting grassland to arable land is to be viewed very critically, for reasons such as protection from climate change. Whenever grassland is ploughed up, a considerable part of carbon stored in the soil is released to the atmosphere in the form of greenhouse gases. This applies above all to grassland on organic soils which are particularly rich in high proportions of organic matter. The conservation of grassland is therefore highly relevant also in terms of climate protection. Furthermore, grassland plays a major role in species protection, the conservation of biological diversity and the protection of soils and water bodies.

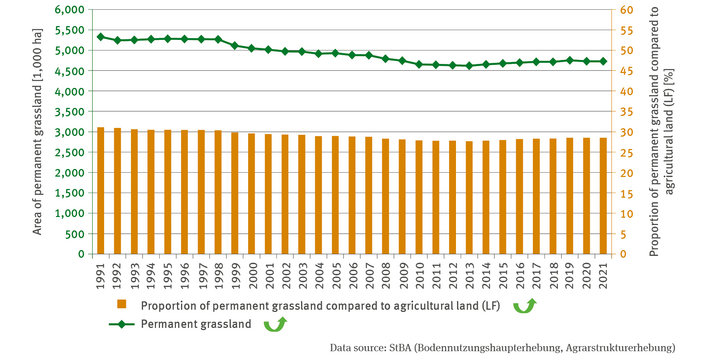

The total of Germany’s grassland terrain decreased between 1991 and 2013 by roughly 700,000 ha. Of 5.3 million ha originally, only some 4.6 million ha were left by the beginning of the 2010s. This development – apart from the task to make use of terrain with unfavourable production conditions – was the outcome of grassland conversion in favour of the cultivation of food crops, animal feed or the cultivation of renewable raw materials. Regions which in those days suffered the greatest

absolute losses of grassland – such as Bavaria and Lower Saxony – are in part characterised by intensive livestock farming. However, the relative losses were partly also significant in other Länder where grassland use is less widely distributed. The intensification of dairy farming and low milk prices prompted agricultural businesses to tend predominantly high-performance dairy cows. Their basic food consists of grass, hay and silage, with the addition of major quantities of concentrates by means of cereals and protein carriers such as soy- and rapeseed meal. Moreover, the regions affected also experienced the most extensive increase in biogas capacities – with impacts on the conversion of grassland terrain by ploughing. It can therefore be argued that up until 2013, the nationwide decline of grassland was almost proportionate to the decline of agricultural land in Germany overall. Presumably, this occurred because a great deal of moist grassland was ploughed up and then drained. It can be said that ploughing activities on wet soils or moorland soils have therefore been particularly alarming in terms of climate protection.

Since 2013, there has been an increase in the terrain of permanent grassland. Likewise, the proportion of grassland compared to the total agricultural terrain increased by 2019. Over the last three years of the time series, this proportion consistently amounted to 28.5 %. The EU’s agricultural reform is seen as one of the reasons for the reversal of this development in the mid-2010s. This reform was adopted by the Council of Europe and the European Parliament at the end of 2013. In subsequent years, the new regulations were incorporated by the individual member states into their respective national legislations. In Germany, for example, the permanent grassland conservation precept was in force from 2015 to 2022 within the framework of ‘Greening’. It continues to be in force for the new CAP funding period which began in 2023 within the framework of the GLÖZ Standard. This means that any funding disbursed to agricultural businesses from the CAP is conditional on ensuring that the permanent grassland terrain as a proportion of agriculturallyused terrain in a defined region does not suffer anydecline. The conversion of permanent grassland to arableland should in principle be allowed only with official authorisationand, depending on the site’s location and ageof the permanent grassland, this should only be tolerated on condition that new permanent grassland be created elsewhere. In some Länder such as Schleswig-Holstein, Mecklenburg-Western Pomerania and Baden-Württemberg, there are specific legal regulations in force, passed by each of these states which prohibit in principle any conversion of permanent grassland to arable land. As of 2023, the new CAP funding period is valid not just in areas designated according to the Habitats Directive (FFH areas). This means that a strict ban on ploughing and conversion is in force, not just for permanent grassland but also for bird sanctuaries, wetlands and moorlands.

Any newly created grassland can contribute to the additional sequestration of carbon, as a rule regardless of its composition, as this grassland is certain to further humus production. However, with a view to biodiversity it has to be borne in mind that newly created grassland is typically more species-poorer than long-established grassland terrain. It follows that within the framework of the grassland conservation precept, the newly created grassland is less significant than the conservation of

older terrain of this kind105.

105 - BfN – Bundesamt für Naturschutz (Hg.) 2017: BfN-Agrarreport 2017 – Biologische Vielfalt in der Agrarlandschaft. Bonn-Bad Godesberg, 61 pp. https://www.bfn.de/publikationen/bfn-report/agrar-report