Herring fishing has a long tradition in Germany and is of major importance regionally. Particularly in Mecklenburg- Western Pomerania the herring is considered a food staple. On average this species accounts for roughly 70 % of catch contents in this area.86 Likewise, the Atlantic herring (Clupea harengus L.) is internationally a fish species of great economic importance.

Moreover, the species is of central importance to the Baltic Sea ecosystem: For porpoises, Atlantic grey seals and fish-eating seabirds, the herring is an important food source. Moreover, it has its place in the food chain between plankton – its own food source – and the carnivorous predatory fish. The herring shares this position with only one other fish species – the sprat. If herring stocks in the western part of the Baltic Sea were to collapse, the food chains of this ecosystem would have to depend solely on the stocks of sprat.

Contrary to other stocks, occurring, for instance in the North Sea, herrings in the western part of the Baltic Sea spawn in spring. In order to deposit their eggs, herrings migrate from their wintering grounds in the Oresund, to their spawning grounds. These locations are primarily in the Greifswalder Bodden and the Strelasund – the strait between the island of Rügen and the mainland. This is where the spawn is deposited on certain aquatic plants in shallow water. After hatching the herring larvae first feed on their own yolk sac. Once this has been consumed, they feed on zooplankton, such as the larvae of copepods.

The water temperatures influence herring reproduction in various ways. This stage is also known by the term ‘recruitment’ in fisheries. On one hand, water temperatures determine the point in time when adult herring leave the Oresund to migrate to their spawning grounds. If a certain water temperature is reached at an earlier time in the year, herring migration will begin earlier. On the other hand, temperatures influence the time of egg deposition as well as the speed at which the eggs develop. Likewise, herring larvae grow faster in warmer waters owing to their metabolism speeding up. As a result, the larvae depend earlier on external food – zooplankton – and their need of food increases.

Although further research is required in respect of the relationships described, scientists maintain that the herrings’ changed phenology leads to the decoupling of their progeny from their food source owing to loss of synchronicity, as the development of zooplankton – according to current findings – is influenced by light rather than warmth. In other words, their food source is not available any earlier in the year than before and therefore not as early as it is required by the herring larvae owing to changed water temperatures. Consequently, having hatched too early plus developing faster, the herring larvae are exposed to starvation87.

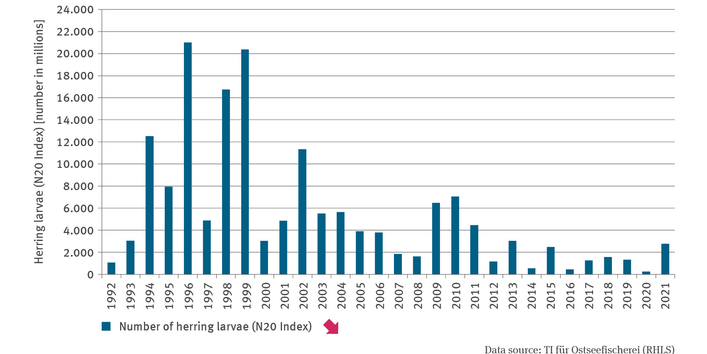

The indicator used for herring recruitment success in the western part of the Baltic Sea is the ‘N20 Index’. This index is based on the findings of the Rügen Herring Larvae-Survey (RHLS), which has been conducted by the Thünen-Institute for Baltic Sea Fisheries since 1992, in order to identify the abundance of herring larvae stocks in the Greifswalder Bodden area. In fact, this index represents the modelled total of herring larvae which, by the end of the spawning stage, have reached a body length of 20 mm. Among other things, the index provides an important basis for recommendations submitted by the International Council for the Exploration of the Sea (ICES) regarding fishing quotas for herring in the western part of the Baltic Sea.

Since the early 2000s the number of herring larvae in the Greifswalder Bodden area has declined drastically. Even prior to that, herring progeny had suffered several bad years. This is true for 1992 and 1993 when recruitment was not very successful. The winter of 1991 / 1992 was unusually mild, followed by comparatively warm weather in spring 1992. However, in the 1990s, the impacts of this phenomenon were always short-lived. Nevertheless, larvae numbers have been relatively low – even in the better years – since the beginning of the 2000s.

Apart from the decoupling of herring larvae from their food source owing to asynchronicity – which is seen as the key influential factor responsible for the herring’s declining recruitment success – there are other factors influencing herring reproduction in the western part of the Baltic Sea. For example, there has to be an adequate growth of aquatic plants for herring to deposit their spawn. However, the nutrient inputs into the Baltic Sea, caused by human activity, lead to a reproduction boom in algae unsuitable for oviposition, thus displacing the plants required for spawning purposes. Suitable aquatic plants grow increasingly in very shallow water. However, spawn is more exposed to spring storms in these locations and thus destroyed more easily. If the intensity of storm surges were to increase as a result of climate change (cf. Indicator KM-I-3), this development would be particularly unfavourable. Moreover, owing to nutrient surpluses in the Baltic Sea, there is an increased occurrence of several species of algae which are poisonous to herring eggs. Furthermore, it can be assumed that owing to the shortage of food supply, herring larvae – having to search for food more actively than in the past – are more likely to fall prey to predators.

Last not least, the pressure exerted by fishing activities plays a part. If fewer adult herring were caught, the chances of successful recruitment would be greater. In that light, the fishing quotas for the protection of stocks in the western part of the Baltic Sea were heavily curtailed in recent years, albeit at a later point in time than had been recommended. In the meantime, a ban has been issued regarding the targeted fishing for herring, although there are exceptions in force for the small coastal fisheries provided that passive fishing equipment is used such as set nets and pots. The ICES scientists had recommended fishing bans long ago arguing that these measures would allow stocks to recover within a few years provided fishing pressure remained low thereafter. However, it is unlikely that the size of fish stocks existing in the 1990s will ever be seen again.

86 - LALLF – Landesamt für Landwirtschaft, Lebensmittelsicherheit und Fischerei Mecklenburg-Vorpommern (Hg.) 2021: Fangstatistik der Kl. Hochsee- und Küstenfischerei M-V 2012–2021. Fanggebiete: Nord- und Ostsee. https://www.lallf.de/fileadmin/media/PDF/fischer/5_Statistik/Fangstatistik_10Jahre2021.pdf.

87 - Polte P., Gröhsler T., Kotterba P., Nordheim L. von, Moll D., Santos J., Rodriguez-Tress P., Zablotski Y., Zimmermann C. 2021: Reduced Reproductive Success of Western Baltic Herring (Clupea harengus) as a Response to Warming Winters. Frontiers in Marine Science, 8: 589242. doi: 10.3389/fmars.2021.589242.