Spree faces increased water shortage after coal phase-out in Lausitz region

A new study for the German Environment Agency (UBA) foresees enormous tasks for the water supply along the Spree River if significantly less groundwater is pumped into the river with the end of brown coal mining in the Lausitz region. According to the study, in dry summer months this can lead to up to 75 per cent less water in the Spree locally - with corresponding consequences for the Spree Forest, its lakes and canals, and the drinking water supply in the Berlin region. UBA President Dirk Messner: "In the worst-case scenario, water could become severely scarce in Berlin and Brandenburg if decisive countermeasures are not taken. The states of Brandenburg, Berlin and Saxony face similar challenges. They should quickly tackle them in cooperation with the water industry." The study suggests, among other things, that dams and water reservoirs be upgraded and existing lakes be expanded to act as water reservoirs. The federal states should also jointly explore how water from other regions can be pumped into the Spree through new pipe systems in a way that is as environmentally sustainable as possible. Households, industry and agriculture should also save more water. One option, if necessary, would be to continue pumping groundwater for the time being and to channel it into the Spree in a purified form.

Mining in the Lausitz has artificially increased the water runoff in the Spree for more than a century. This is because groundwater was pumped out for brown coal mining and fed into the Spree. The current drinking water supply in Berlin is partly based on this water. However, the phasing out of brown coal mining by 2038 at the latest, which is necessary for climate policy, will fundamentally change the water balance of the entire region. However, the threat of water scarcity is no reason to abandon the coal phase-out, says Dirk Messner: "Climate change is the biggest problem we face. It is already creating droughts and weather extremes. Coal mining has been harmful to the environment for decades. I am absolutely in favour of continuing to aim for a 2030 phase-out for Lausitz, otherwise we will struggle to meet our climate targets."

Since the beginning of brown coal mining in the 19th century, around 58 billion cubic metres of groundwater - more than the volume of Lake Constance - have been extracted by mining and discharged into the Spree. About half of the water carried in the Spree by Cottbus comes from pumped groundwater. In hot summer months, this proportion rises to up to 75 percent, according to the results of the published study.

For the section of the Spree in Saxony, the forecast assumes an annual water deficit of around 95 million cubic metres. In the lower reaches of the Spree in Brandenburg, there will probably be a shortfall of around 126 million cubic metres per year in future - more than three times as much water as the Müggelsee (Berlin's largest lake) can hold.

If water demand remains the same or even increases, there is a risk of increasingly frequent and prolonged water shortages in the region, especially in dry years. The increasing water shortage affects, among other things, the raw water supply for Berlin's largest drinking water plant in Friedrichshagen. The dilution of Berlin's treated wastewater with Spree water – about 220 million cubic metres per year – is also becoming increasingly problematic. At the same time, an additional six billion cubic metres of water will be needed in the coming decades just to fill the opencast mining holes so that they do not become unstable. The water deficit will be exacerbated by the consequences of climate change.

The study examined the water management consequences of the brown coal phase-out in Lausitz in detail over several years. Associations, competent federal and state authorities, local politicians and civil society were widely involved. As a result, several solution options emerged on how to address the water shortage - they are an invitation to the politicians of the affected federal states to tackle concrete solutions for the region on the ground. In detail:

Saving water: All user groups in the region will have to save significantly more water in the future. Meanwhile, the projected water deficit will not be compensated for by savings alone.

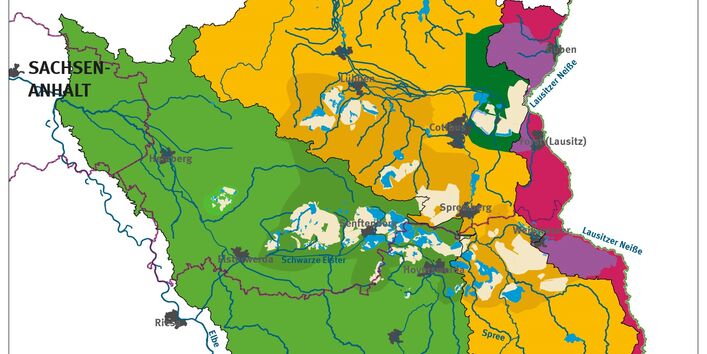

Transferring water: In order to compensate for the projected water deficit, it is essential to provide additional water for the river basins of the Lausitz region. The study advises water transfers from neighbouring rivers such as the Elbe, Lausitzer Neiße and Oder. This would require the construction of the necessary nature-compatible infrastructure, which will take some time.

Expanding storage facilities: So far, the region has a storage volume of around 99 million cubic metres of water. With an expansion of the storage capacities by 27 million cubic metres, deficits in the water-scarce months could be partially absorbed, provided that the stored water volume is available without restrictions; the existing storage volumes can currently only be used to a limited extent by about 50 percent. First of all, therefore, existing reservoirs must be renovated and upgraded in order to be able to use their full capacity. Mining lakes could also serve as water reservoirs. For this purpose, the study suggests the Cottbus Ostsee. However, this would require the immediate creation of the necessary legal preconditions for storage use.

Discharging groundwater: A purely temporary (emergency) solution could be to continue operating the pumps from the mining operations. For one thing, this would have negative ecological consequences, as it would further increase the sulphate contamination of the Spree. Furthermore, the treatment of the pumped groundwater is supposedly the most expensive solution to compensate for the water shortage compared to other measures.

Under these worsening conditions for its drinking water resources, Berlin in particular will be forced to reorganise its water supply. The Berliner Wasserbetriebe (Berlin Water Company) and the Senate are already working on corresponding concepts.

In view of the great challenges, the UBA recommends developing a master plan that spans the federal states for the region's water management. The affected federal states of Saxony, Brandenburg and Berlin must jointly and immediately develop sustainable concepts for water use for the time after the coal phase-out. The various user groups such as industry, agriculture, tourism and water supply must be included in this process.