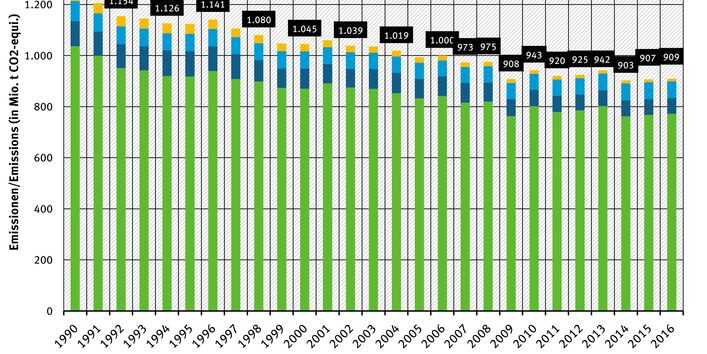

Greenhouse gas emissions rose again in 2016

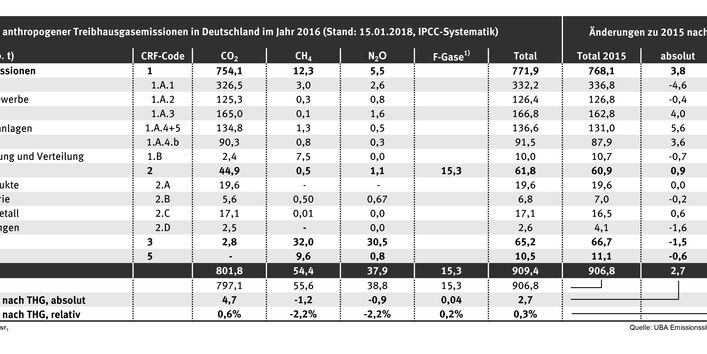

In 2016, German emissions reached a total of 909.4 million metric tonnes CO2 equivalent. This amounts to 2.6 million tonnes more than in 2015 and represents the second increase in successive years. Such are the results of calculations recently submitted to the EU by the German Environment Agency (UBA). Emissions from the transport sector have risen once again and, at 166.8 million metric tonnes, again exceed the levels of 1990. The lion's share of these emissions is accounted for by road traffic, which rose by 3.7 million metric tonnes. The reason for this is that ever larger quantities of goods are being moved by road. Moreover, the trend towards ever larger and heavier cars continues unabated. “We need to turn things around in the transport sector: According to the climate protection plan of the German Federal Government, traffic emissions are supposed to decline by some 70 million metric tonnes by 2030. If cars become significantly more energy-efficient and we are given a quota for electric cars, this is not beyond the bounds of possibility. But the legislative framework is not yet in place. We therefore recommend that, as of 2025, the EU should above all not permit emissions of more than 75 g/CO2 per kilometre in average across the fleet for new car registrations. The current draft of the Commission for CO2 limits for passenger cars is too lacking in ambition," said UBA President Maria Krautzberger.

The largest reduction in CO2 emissions, at 4.6 million metric tonnes, has been achieved in the energy sector, notwithstanding an increase in exports of electrical power. At 332.1 million metric tonnes per year, however, most of the emissions are accounted for by the energy sector (36.5%). “If we want to get anywhere quickly with climate protection, we're going to have to deal with the problem of coal-generated electricity. I would also advise setting a limit of no more than 4000 full-load hours per plant per year for lignite and hard coal plants which are older than 20 years. What's more, at least 5 gigawatts of the oldest and most inefficient coal-fired power plants should be shut down completely.” said Ms Krautzberger. “And if we're going to meet our climate targets by 2030, it's crucial that the energy sector should account for much of the reduction. But this will only happen if we quickly get on with decommissioning older and inefficient lignite and hard coal power plants. Otherwise we run the risk not only of missing our climate goals for 2020 but also of getting into trouble all over again at the end of the next decade.” In 2016, Germany succeeded in reducing its emissions by only 27.3% in comparison to 1990 levels; the Federal Government had originally set the goal of a 40% reduction for 2020, which is likely to be missed by some margin.

The emissions brought about by heating buildings rose for weather-dependent reasons by a further 3.6 million metric tonnes in comparison to 2050, as more energy was required for heating. Ms Krautzberger said : “When it comes to buildings, there is enormous potential for making savings, whether by means of more efficient thermal insulation, overhauling old central heating systems or through using renewable energies.”

In agriculture, emissions fell slightly in 2016 in comparison to the previous year, to 65.2 million metric tonnes. The scaled-back use of mineral fertilisers was crucial to this reduction. However, industrial emissions increased slightly, by 1.4 per cent, due in particular to the growth of the metals industry.

Emissions by greenhouse gases

In 2016, carbon dioxide (CO2), with a share of 88.2%, was once again the leading greenhouse gas, generated mainly by the combustion of fossil fuels. The remaining emissions were divided between methane (CH4), at 6 per cent, and nitrous oxide (N2O), at 4.2 percent, which were principally generated by agriculture. Compared to 1990, emissions of carbon dioxide fell by 23.9 percent, of methane by 54.4 per cent and of nitrous oxide by 41.1 percent.

Fluorinated greenhouse gases (F-gases) cause a total of only about 1.7 percent of greenhouse gas emissions, but have very high global warming potential. Here, the trend is less uniform: As a result of the introduction of new technologies and the use of these substances as substitutes, the emissions of sulphur hexafluoride (SF6) and hydrofluorocarbons (HFCs) have declined since 1995 by 40 and 87.5 percent respectively. In the same period, emissions of halogenated hydrofluorocarbons have risen by 31.1 percent. Emissions of nitrogen trifluoride (NF3) increased slightly after 1995, by 110.7 percent, but have decreased again rapidly since 2010.