Environmentally Harmful Subsidies: nearly half granted for road traffic and aviation

The phasing out of tax breaks for automobile and agricultural diesel, the private use of fossil-fuel company cars and agricultural vehicles, as well as of the commuter mileage allowance would generate additional revenues for the public sector in the double-digit billions. This is the conclusion of a new study by the German Environment Agency (UBA) on environmentally harmful subsidies in 2018. These subsidies can be abolished at national level. Tax breaks for jet fuel and the VAT exemption for international flights account for another twelve billion euros. However, this would have to be addressed at the European level. "It is a paradox when the state spends many billions to promote climate protection while it subsidises production and behaviour patterns that are harmful to the climate. We all know that time is running out with regard to climate protection, which is why we must make rapid progress in reducing environmentally harmful subsidies. This will relieve the burden on public budgets and enable climate-friendly investments, which must be made with a sense of proportion for the social and economic consequences, said UBA President Dirk Messner.

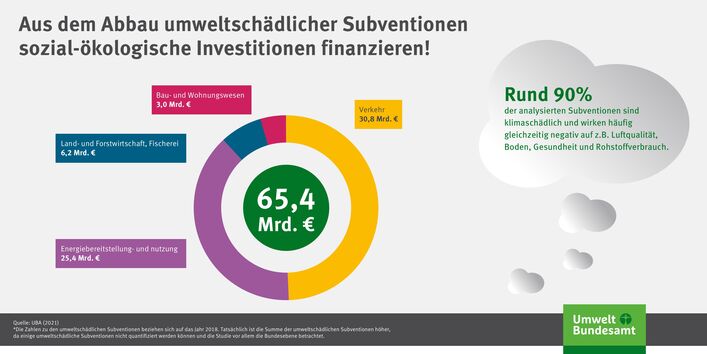

Almost half of the environmentally harmful subsidies identified by UBA in 2018 were in the transport sector (47 per cent), 39 per cent in energy supply and use, nine per cent in agriculture and forestry, and five per cent in construction and housing. In fact, the total of environmentally harmful subsidies is higher than the €65.4 billion estimated for 2018 as a whole, as some environmentally harmful subsidies cannot be quantified and the study mainly looks at the federal level.

Environmentally harmful subsidies hamper the development and market breakthrough of environmentally friendly products and jeopardise environmental and climate goals. They also make environmental and climate protection more expensive because the state has to promote both more strongly if it subsidises environmentally harmful products and processes at the same time. " Economic incentives are currently being set in opposite directions - sometimes for, sometimes against environmental and climate protection. An example of this is the pointless parallel existence of diesel privileges for internal combustion engines and purchase premiums for electric cars," said Messner.

Since the last estimate in 2012, there has been little progress in reducing environmentally harmful subsidies. In the meantime, some subsidies have expired (e.g. for hard coal extraction), but new ones have been introduced in parallel. In transport, subsidies actually increased from 28.6 to 30.8 billion euros between 2012 and 2018. This is at odds with the increase in subsidy programmes for climate and environmental protection in recent years. Around 90 percent of the subsidies analysed are harmful to the climate and often have a negative impact on air quality, health and raw material consumption.

Subsidies worth 65.4 billion euros in 2018, as reported in the study, are not identical with the additional financing scope gained for the public sector in the event of a reduction. The dismantling of environmentally harmful tax concessions, for instance, can lead to environmentally desirable adjustment reactions that reduce tax revenue. For example, an increase in the energy tax rate on diesel increases the incentive to save fuel and switch to e-vehicles. It is sometimes advisable to phase out subsidies gradually so that the funds are only available in part immediately. Also, dismantling subsidies requires accompanying measures to cushion the social and economic consequences, which can tie up large parts of the freed-up funds.

Some major environmentally harmful subsidies can only be partially dismantled at the national level. One example is the jet fuel tax exemption on domestic and non-European flights. The EU Commission's current plans envisage gradually including aviation and shipping in energy taxation and taxing diesel and petrol uniformly according to their energy content. This would significantly advance the phase-out. "The German government should use the backing from Brussels and push for an ambitious reduction of environmentally harmful subsidies at EU level," says Dirk Messner. International agreements on CO2 pricing or the introduction of CO2 border adjustment mechanisms could also make those subsidies superfluous that have so far protected domestic industries from environmental dumping.

The UBA study contains proposals for reform on how subsidies can be dismantled. In the housing sector, in energy-related subsidies for business or in agriculture, it is not primarily a matter of reducing the overall volume of subsidies but rather to restructure the subsidies in such a way that they mobilise investments for the socio-ecological transformation and facilitate environmentally sound living.

In some cases, the dismantling of environmentally harmful subsidies makes sense because they are inefficient and the original subsidy objectives have lost their meaning – the lower energy tax for agricultural diesel and the motor vehicle tax exemption for agricultural vehicles, to name a few. Other environmentally harmful subsidies should also be dismantled for reasons of social justice. One example is the private use of company cars, which the state subsidises to the tune of at least three billion euros per year. "This mainly benefits households with high incomes. This subsidy is not only harmful to the environment, but also socially unjust. It should be abolished," says Dirk Messner.

Money that is freed up by reducing environmentally harmful subsidies must be used to help companies switch to greenhouse gas-neutral production methods. The state must also use the money released to relieve the burden on private households. A reform of the commuting allowance, for example, would require a solution that both ensures social compatibility and enhances the positive environmental impact. Particularly important would be a hardship clause for long-distance commuters and the massive expansion of local public transport, especially in rural areas. The reduction of the low VAT on meat and other animal products, which UBA considers advisable, would also have to be flanked and embedded in a comprehensive reform of VAT that relieves citizens in other areas – for example, through a low VAT on fruit, vegetables and other plant-based foods as well as cheap bus and train tickets.

To ensure that environmentally harmful subsidies are systematically reduced or reformed in the future and that subsidy policy becomes more effective and efficient, the UBA study formulates guidelines for an environmentally oriented subsidy policy and recommends an "environmental check" for all subsidies. In principle, only subsidies that are in line with sustainable development should be granted. Henceforth, in order to ensure this, there should always be a check to see whether there are more environmentally friendly alternatives for the subsidy.